TLDR: We have a lot of Python code and in this post we announce some resources we have open sourced that has resulted from a large effort to make it strongly typed 1.

Here at Kraken we have a lot of code written in Python and the Django web framework. Including tests our main monorepo is well over 10 million lines! When we exclude blank lines and comments, there are 5 million lines of Python that we run Mypy over. Our codebase existed for many years before the Python ecosystem had any kind of static type checking, and so there’s a lot of catching up for us to do to turn it into a strongly typed codebase.

The landscape - Django’s compatibility with mypy

The biggest challenge we face is that Django does not have its own Python annotations, and has made architectural decisions that make it very difficult to make static guarantees.

There are two primary projects to resolve this problem - Django stubs, and django types.

Both these projects provide .pyi files that a static type checker can use to understand the shape

of Django itself, but the former also comes with a mypy plugin that does some custom analysis at

type checking time. This custom analysis is achieved by bootstrapping the Django application and

using Python runtime introspection to understand what the code would be doing to be able to then

make static guarantees.

A good example of this is reverse foreign key relationships on Django ORM models. This feature means that there are dynamic attributes on some models depending on the existence of other models. We can statically know this if we know about all the models that exist, but without that knowledge, the static type checker cannot possibly know about those attributes.

The way that Django types solves this is by encouraging developers to manually add annotations to represent them. The problem with this is we have over 2000 Django models with complex relationships that change across teams. Keeping those annotations in sync and accurate is effectively what we’re doing with the Django stubs mypy plugin.

This does lock us into mypy given it’s currently the only static type checker for Python that supports plugins, but it’s a very large codebase and we do get real value from the extended coverage that gives us.

Concrete Django models - We made our own mypy plugin

Another challenge we face is around how Django ORM uses abstract models and the way we use them to represent common functionality that are extended for each client we serve. There are some efforts internally for these scenarios to be done differently, but they will be long term efforts and we need to support a lot of code in the meantime!

This became a blocker to us upgrading to newer versions of mypy, and after a few different attempts we landed on creating a mypy plugin that takes the Django stubs plugin and adds some extra functionality to it. That can be read about in this Github discussion post.

In short, the Django ORM has the ability to define some of the columns in a database table, and then uses inheritance to define “concrete” models that represent the full table in the database. We want to take references to those “abstract” models and get back a union of all the “concrete” models that could exist. This has the same requirement as everything else the Django stubs mypy plugins offers in that we need to know all the models that exist, and so it is a natural approach to get that information at type checking time. It was a challenge to solve these issues, but we did and we were able to get our codebase onto the latest version of mypy without adding 1000s of type ignore comments!

That plugin is open source and as mentioned in the above link to django stubs’ discussion board, can be found at at it’s repository page on Github.

Guarantees and annotations - How we ensure Django views are annotated correctly

Static typing in Python is one of those things that’s extremely easy to start doing, but far less easy to do well. A really good example of this is adding annotations for Django views.

class MyView(generic.View):

def get(

self,

request: http.HttpRequest,

**url_args: object

) -> http.HttpResponse:

...

This is fully annotated! But are those annotations useful? Does it actually give us any static

guarantees? I’d argue it doesn’t provide enough value. I repeat often when explaining static typing

to my colleagues that the key is to understand that type annotations cannot represent dynamic

behaviour (except via a mypy plugin!) and fundamentally the shape of this url_args object is only

determined by the url pattern the view is used with. Additionally, with a Django view class like

above, it’s the implementation of the as_view classmethod that actually determines what is given

to this method.

So if this view appears in a url pattern like this:

("/things/<thing_id:int>", MyView.as_view())

Then using our knowledge of the implementation of as_view on the generic.View class, we know

that the get method will always get:

class MyView(generic.View):

def get(

self,

request: http.HttpRequest,

*,

thing_id: int

) -> http.HttpResponse:

...

There’s a number of these kinds of guarantees that we can make via introspection of our views and URLs. We do want to move away from mypy at some point in the future, ideally to Astral’s type checker, so betting on plugins at this point feels like the wrong bet to take. Therefore we instead rely on a Pytest test that performs that introspection and checks the annotations on our views match the urls the views are used with.

We have open sourced this code as the django-consistency-enforcer package and is designed specifically to be flexible to the demands of each project it is used with.

Using this we can ensure that the annotations for the request object, the url args and the authenticated user object that we give our views are useful and are enforced as consistent and correct in an environment that is constantly evolving and modified by hundreds of developers across the world.

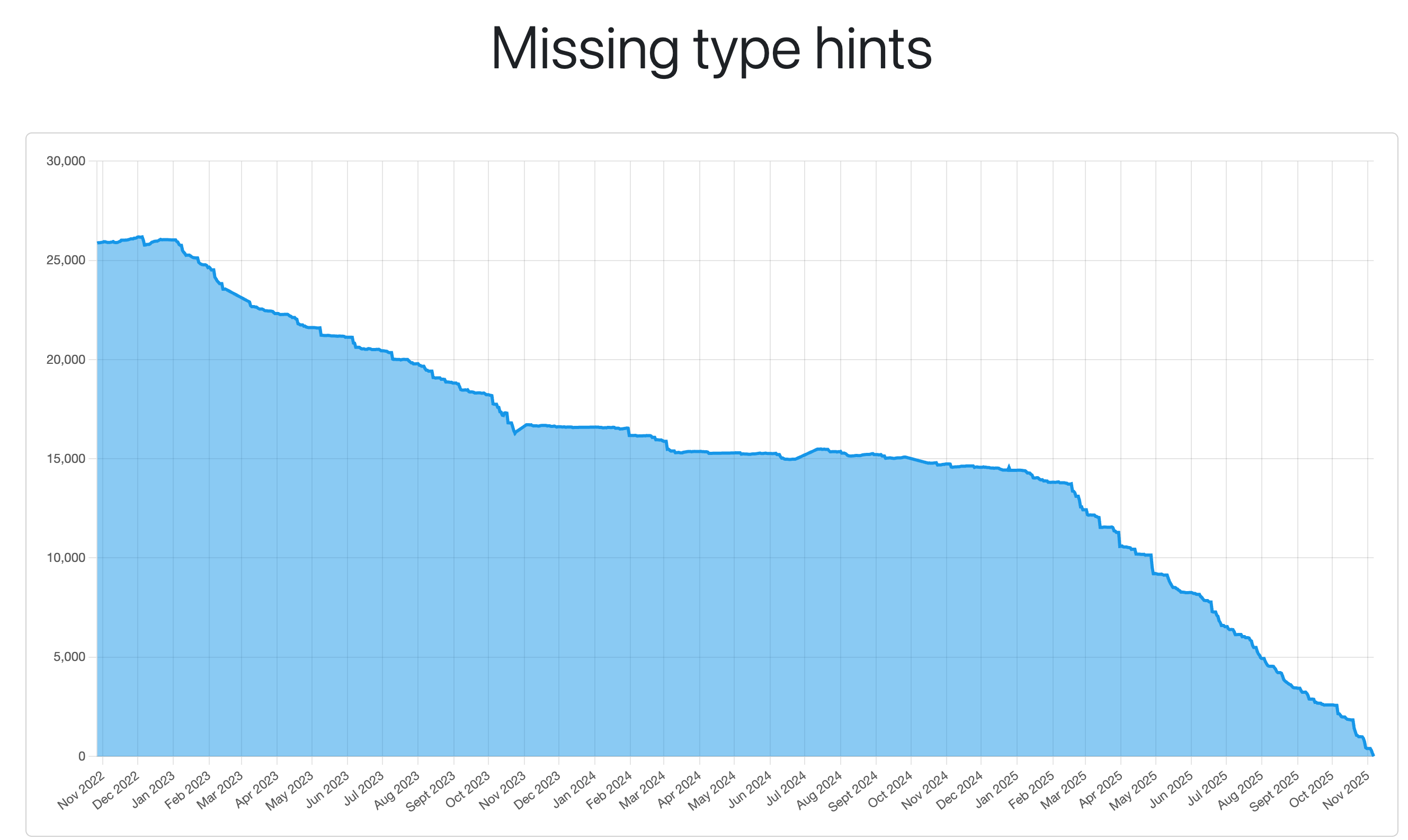

Fully annotated - burning down 25k missing annotations over 2.5 years

It wasn’t straight forward, but after upgrading mypy and Django, making a django plugin, and a huge number of changes to the codebase over 2.5 years, we have achieved a giant milestone in our path towards a strongly typed codebase - and reached zero missing annotations!

There’s still a lot of code that is considered Any at static time

(mypy’s way of saying something is ignored by the type checker) but with only 5k type ignores and an

effort that actively tried to avoid throwing the Any annotation everywhere, we have created a strong

foundation.

That steep slope at the end between Feb 2025 and Nov 2025 was where I was able to dedicate a lot of my time within our developer experience team towards making this our reality. There are many factors that go towards the health of a codebase and a big factor towards that is the ability for changes to be made without undesirable side effects. Having static time guarantees in any language is a very powerful tool to remove a whole class of very silly mistakes without having to write large amounts of mechanical combinatorial unit tests that are highly coupled with the specifics of an implementation.

Writing strongly typed code is more than simply annotating the existing code. The goal isn’t to make the static type checker say there are no errors. The goal is to ensure that the pieces fit together and that the flow of data and logic is coherent and makes sense! Complaining about your code is mypy’s love language, and we want developers to think about the decisions they are making and how those decisions not only affect the code now, but will affect the ability to make changes in the future.

Giving back - opensourcing the tools that helped us

In that spirit, the work to fill out all the annotations also came with creating a resource for our developers to understand how to write useful annotations. We are proud to open source a large amount of that resource. The advice may not be applicable to every project, and there’s some opinions that come from the unique challenges in our codebase, but we hope it’s broadly useful to the wider community.

That resource can be found over on readthedocs: https://kraken-static-typing-advice.readthedocs.io

What’s next - going from annotated to strongly typed

There are many technical challenges in our codebase and the strength of our static typing will continue to be a factor we take seriously. There’s a lot left to do and we can use that work to shape our decisions and the resources we give to our developers. We have an obligation to our clients to make software that is reliable and correct, and we take this obligation very seriously. There’s many factors that leads to a healthy codebase, and static guarantees will be a factor we continue to invest in!

-

The difference between “annotated” and “strongly typed” is where the code being annotated is capable of, and has, annotations that eliminate without coercision or type ignore comments all explicit and implicit

Anytypes (the type mypy uses to ignore code). ↩

Would you like to help us build a better, greener and fairer future?

We're hiring smart people who are passionate about our mission.

- How we ship in 2026

- Django, Kubernetes Health Checks and Continuous Delivery

- Working with async Django: lessons learned

- Making a major RabbitMQ version upgrade without breaking Celery ETA tasks

- Electrifying and flexing low-carbon domestic heating in the home

- Building an AI copilot to make on-call less painful

- Building the largest electric vehicle smart-charging virtual power plant in the world

- How we ship over 100 versions a day to over 25 environments in more than 10 countries

- Avoiding race conditions using MySQL locks

- Estimating cost per dbt model in Databricks

- Automating secrets management with 1Password Connect

- Understanding how mypy follows imports

- Optimizing AWS streams consumer performance

- Sharing power updates using Amazon EventBridge Pipes

- Using formatters and linters to manage a large codebase

- Our pull request conventions

- Patterns of flakey Python tests

- Integrating Asana and GitHub

- Durable database transactions in Django

- Python interfaces a la Golang

- Beware changing the "related name" of a Django model field

- Our in-house coding conventions

- Recommended Django project structure

- Using a custom Sentry client

- Improving accessibility at Octopus Energy

- Django, ELB health checks and continuous delivery

- Organising styles for a React/Django hybrid

- Testing for missing migrations in Django

- Hello world, would you like to join us?